Did Paul Revere Stop Here?

Sometimes, traveling through one’s own country with a companion who is unfamiliar with your national mythos, can be revealing. It can help you peer through the smoke of that mythos, which emanates off the wide floor boards of a founding father’s house, or lies in the dirt of a village common green. To see it as not quite a contrivance, but a kind of chimera just the same, or a costume that we still assume to adorn, even though as Ralph Waldo Emerson once wrote, we sometimes behave as a “living generation into masquerade out of its faded wardrobe.”

It was along the old Battle Road Trail from Lexington to Concord, we rented bicycles to trace the path, which back in 1775, the British Regulars took to Concord to confiscate the rebellious colonists’ armaments. And the same road they took to flee back to Boston, while “the farmers gave them ball for ball. From behind each fence and farm-yard wall.” The New England scenery just along the trail is a lovely woodland landscape, occasionally giving hints to what was once an 18th century pastoral scene. A few of the original farm houses are represented, tucked in amongst the trees. At each stop we made, Fiske Hill, Parker’s Revenge, Bloody Angle, I read the battle description boards while my partner performed a little dance, trying to shoo away potential mosquitos.

We enjoyed a musket firing demonstration at Hartwell’s Tavern by two National Park guides dressed in 18th century garb and tricorn hats. You can’t help but feel a sense of historical significance to the area when you see every mile or so a memorial plaque on a granite boulder declaring that the remains of British soldiers lie nearby in the ground, a couple of Union Jacks stuck in the dirt on either side of the boulder.

We came upon what was designated as the site of Paul Revere’s capture. It was a rather significant monument with a circular low rise stone wall and a large plaque on a hunk of granite. Bronze relief letters explained what occurred here in April 1775. My partner hugged me and kissed me on the cheek and said she was sorry for his loss and that it probably means a lot to me. I looked at her curiously. She was vague on the details of what happened here, I surmised. She isn’t much to reading historical plaques in what is essentially a third language for her.

“Well it’s just where he got stopped by the British,” I said.

“And where he was killed and decapitated, no?”, she asked.

“Oh no, no, he was just stopped from going on to Concord. He was soon released without his horse to walk back to Lexington, or something like that. He survived just fine,” I replied.

I gave a little laugh, but perhaps understood the confusion. It didn’t help there was a cemetery nearby, we had visited the day before, called Sleepy Hollow, where the bones of old story tellers lie. Last year around Halloween I recounted in brief a version of The Legend of Sleepy Hollow to her. Washington Irving’s story is way more than the headless horseman, but that’s the gruesome detail that stands out, itself a ridiculous ghost story that Brom Bones tells Ichabod Crane, within the short story. I remember last year on a brief cruise port stay in Boston, I visited with an old housemate in the North End, that I hadn’t seen in years. We ate baked sweets from Mike’s Pastry in the evening underneath the galloping hooves of the Paul Revere statue on the northeast side of the Old North Church, that church with the steeple that alerted Revere the details of the soldier’s launch on that April night. Not only did I notice the equestrian statue was headed in the wrong direction, away from Charlestown and Lexington, but in the shadows and street lamp light he had an ominous stare. I thought someone could have put a jack-o’-lantern in his outstretched hand, then we’d all have been confused. Even if he still has his head.

But that afternoon as I looked at the memorial to what was essentially a road block, I thought that is peculiar. In most countries or even in this country, a memorial of that stature on a battle field might mark the place of sacrifice. It would be the site where heroes had fallen. Certainly a Son of Liberty like Paul Revere deserved a memorial more impressive than the Revere family’s foot-high, chipped slate, tomb marker at the Granary Burying Ground in Boston. A more substantial marker of granite sits a couple of feet next to it commemorating him alone. So the equestrian statue at Paul Revere’s Mall, which ultimately should represent all the warning riders of that 1775 April night, is honor enough. But the marker of his capture is a peculiar thing. The story of Paul Revere’s midnight ride is an event seemingly inflated beyond perhaps its significance. The 19th century poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow expanded or we might even say truly birthed the mythos with his 1860 poem “Paul Revere’s Ride.” The quote about the farmers giving “ball for ball” in this essay’s introduction comes from that poem. Amongst other things, the poem serves as a form of propaganda to lend urgency to what Longfellow considered was the Northern states’ just cause to free the country of slavery, at the cusp of the Civil War, by recalling that bygone era of the cry of liberty. The poem is not historically accurate, which Longfellow was probably aware. Poets would never claim to be journalists.

Revere himself was familiar with propaganda in his day. He had done the engraving, copied from another engraver, of the so called Boston Massacre, calling it “The Bloody Massacre,” only days after the event. The “redcoat” guards, in the image, are all firing their muskets with cold menace on their faces into a gathering of unarmed civilians. I heard even a tourist guide in his colonial coat and tricorn hat in front of the Old State House, on the very site of that event, telling the tourists how it was really a riot, the young soldiers confused and alarmed as the crowd through stones and oyster shells. Some in the crowd held clubs. It was a powder keg situation and tear gas and riot gear were not yet available to soldiers ordered to keep the peace. But that’s the thing about history. It can be a very hazy story and the deeper you look into it, the more you see the fabrication required to convey it in the brief but potent manner that is digestible to the jingoistic patriot, or the romantic consumer, that we all are at some level.

So this spot of ground along the Battle Road Trail, that saw the briefest of action, is now immortalized. And how do we know this was the very site where he was stopped? Did Revere point it out to someone? Did the two other riders, William Dawes or Samuel Prescott, reportedly stopped at the same spot or vicinity, point it out? And to whom? Why would they do such a thing? To be immortalized? Revere was involved in a militia fiasco in what is now Maine, later during the war, and had charges leveled against him. He certainly had motives to counter doubts of his revolutionary service.

This spot on planet earth in relation to Main Street, Concord, downtown Boston, and the House of Parliament in London, is pretty much the same as it was in 1775, but most everything else about the spot is not. The dirt, the trees, and the landscape for the most part are different. The pavement of the road a few feet away or the suburban housing development a few yards through the trees may be a spot where a minuteman or a British Regular bled to death, but they are now just those things they are now. It’s as if the present, with the power of its here and now suchness, mocks our propping up from decay the physical manifestations of historical record, or should we say historical imagination.

The Traveling Paperback Shades the Perception

During my layover in Boston the year before, I started reading the book Sapiens by the historian Yuval Noah Harari. I’m not sure if he coined the phrase “romantic consumerism,” but his book introduced me to the concept. The essential thesis of the book, that so many of the concepts and identities that we use to define our lives are essentially fictions, colored how I experienced the trip. But beyond that, I’ve been for many years, before I ever heard of Harari, engaged in the same psychological or we could say spiritual discipline, called vipassana meditation, as the author. Among the many qualities that vipassana gives the practitioner, there is a tendency to deconstruct one’s experience. To see how past events, experiences, and conditions affect what we see and find significant in the present. And one also sees the nature of the mind to prop up stories and maintain them, all out of fear that without them, we won’t know what we are, and we will become irrelevant, like an abandoned house no longer suited for human habitation.

Signs of Life at the Ralph Waldo Emerson House

On the previous day when we rolled into Concord we stopped at the Ralph Waldo Emerson House, a literary contemporary of Longfellow. They both maintained mutual sympathies with the Union cause in the Civil War era. There is a strange type of melancholy in a house preserved in the state it was when it housed its famous occupants. It’s a kind of mannequin, a wax figure of what it once was. Emerson’s actual walking sticks are there in the foyer. There’s a photograph of him holding one. This is the wash basin where he splashed his face every morning. The photograph of his friend Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner hangs possibly where he once hung it. The bust of Emerson by Concord sculptor Daniel Chester French sits in a corner of the stairwell. Henry David Thoreau assisted as a handyman and gardener here. Many a famous literary figure sat in the study with Emerson. Historical figures like Frederick Douglass or even John Brown, likely sat on a sofa or a chair across from the table that sits before us. But somehow, as we are escorted more or less perfunctory through the passing rooms, the ambiance of such momentous scenes does not much stick to us. We are initially like Teflon to any feelings of inspiration that might bleed off of the walls. It’s only after a lively informed guide on the second floor tour brings up Emerson’s abolitionist friend Sumner and his caning on the Senate floor, that I feel like I’m engaging with artefacts of history. It’s a piece of political and civil war history I was intrigued with at one time. It takes this kind of intriguing story to connect me to the objects I’m encountering.

Of course it’s the story, and the mythology, you bring to a place that makes it inspire. I admittedly am not so familiar with the writings of Emerson. I read his essay Nature a few years back. Found it wordy and hard to decipher. I know he is an influential American writer and an inspirer to many an American artist and intellectual. Even in grade school you here about the Transcendentalists. I remember I liked the word. Even a kid has a hunch that the word indicates a higher plane, where we should spend more of our time, if we are fortunate enough to discover that plane. Someone else coming to that house may have been instantly transported, depending on how steeped they were in the writing and life of Emerson.

A Childhood’s Patriotic Imagination

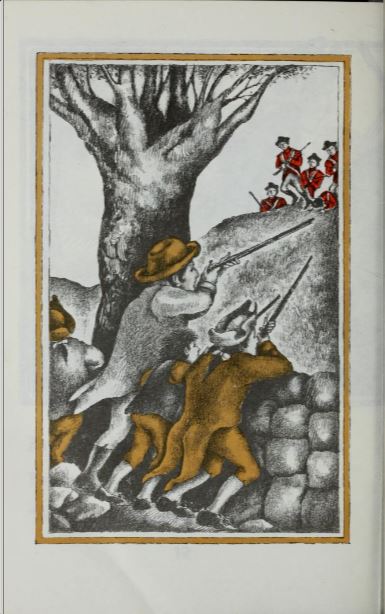

I certainly brought an American’s imprint to that Battle Road Trail. One of my favorite books when I was just learning to read something beyond Harold and the Purple Crayon, was Sam the Minuteman. I remember being fearfully drawn to the page where the young hero’s friend John bleeds from his leg after getting hit on the Lexington green. Whether or not Massachusetts fathers would bring adolescents to a potential battle you may question, but it’s the premise of the story anyway. The book’s illustrations are a mono or two tone color scheme, except for the color red on the backs of those belligerent red coats, and that bleeding wound. I felt pangs of patriotism as we traversed the road once lined with stone fences, as depicted in that young reader’s book, behind which hung minuteman taking potshots at fleeing and falling invaders. But even with that layer of American mythos in my consciousness, in my ordinary awareness of the place, there is still a kind of divine mundanity that wants to assert itself, and make this hallowed ground a little more relatable to who and what we are in the here and now.

There is a kind of rivalry in the heritage traveler’s spirit between our imagination of the past and the reality of the present. The space where that rivalry meets and throws up sparks, is where the experience truly shines. That spark usually comes from spontaneous circumstances that were not expected.

Near the end of the our bike ride along the Battle Road Trail it started to rain. At first just a sprinkle and then in sheets as we passed Nathanial Hawthorne’s house, the Wayside, and Louisa May Alcott’s Orchard House. My partner donned a small red tarp she fashioned into a poncho. It was warm summer rain so I let myself get thoroughly soaked. By the time we reached the Old Manse it came down so hard we had to stop. As I crouched underneath the weak protection of a maple tree the sun suddenly broke out and the Massachusetts downpour was no more. It was then we realized we’d reached our destination and the sunshine sparkled on the Concord River as we walked across the Old North Bridge, the place where the real rebellion began back in 1775. Or at least according to today’s Concordians, in opposition to the opinions of the Lexingtonians. My partner was still wearing her red poncho and from a distance she looked like a redcoat standing on the bridge. In the end though, the exhilaration we felt, certainly partially a product of my inbred patriotism, was heightened by reaching this historical spot in such fashion. My red tarped companion kept raising her fist and yelling, “We’ve had enough!” and “We’re not going to take it anymore.” She was apparently swept up in the patriotic rebellious spirit the place commemorated.

Cannoli and Battle Greens

There were many experiences of this type that made our romantic consumerism seem uniquely our own. My partner gourmandized on the newly discovered wonders of the cannoli from a box of North End shop pastry, as she sat on a bench on the edge of the Lexington Battle Green. She knew the place held some sort of significance, the statue of the minuteman peering down Massachusetts Avenue perpetually waiting for the arrival of the redcoats, attested to that. I’ll remember our visit to the green as much for the delight of this immigrant relishing Boston Italian pastry, as for the mystique of this consecrated ground. The juxtaposition made it both reverent and whimsical. Later on I saw a couple sitting on the grass in the middle of the green eating sandwiches. And why not? It’s also the village’s commons.

Historical Structures Still In Service

I had a stronger kinship with those historical sites and buildings that were still utilized for their original purpose or were repurposed in some way to serve the needs of the living, beyond just the historical artefact. Of course Fenway Park’s historical significance is much younger than say the Old State House, yet we still felt we were indulging in baseball history by attending a game at the oldest Major League Baseball stadium in the US. My partner, originating from a country that also reveres the game, did not have to make any stretches of the imagination to thoroughly enjoy it. It certainly brought back my memories of watching Tiger games at Detroit’s Briggs Stadium. But Fenway Park, when its original use has been exhausted, if radical retrofitting is not available, will not live beyond its original purpose. Briggs Stadium was demolished, as has been the fate of most American MLB ballparks.

But even the Old State House, the original administrative government building of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, dwarfed by the modern buildings around it, had a subway station entrance built below it. Under the gaze of a golden lion and a silver unicorn cresting the facade, potential passengers passed into its walls at the street level to get somewhere else. It served a purpose beyond a museum. Even its museum purposes were not meant to freeze or recall its life as a colonial administrative building. That would have been rather boring. Instead exhibits, that were sometimes obviously updated, provided a history of the independence movement of the 18th century, through the eyes of our contemporary experience. The Boston Tea Party was compared to the June 6th Capital riots or the George Floyd protests.

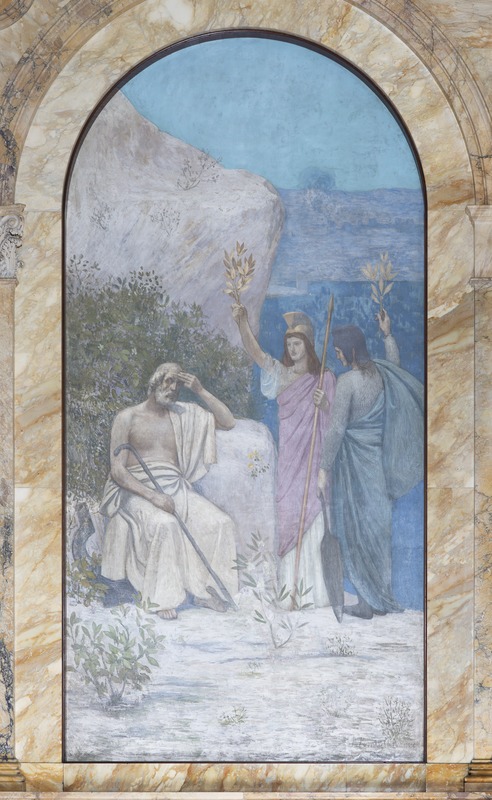

In the Back Bay the La Farge stained glass windows of Trinity Church still illuminate contemporary worshipers. The classical themed murals of Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, biblical prophets of John Singer Sargent, and Arthurian legends of Edwin Austin Abbey, inside the Boston Public Library, hover above both the tourists and the local patrons passing through the stairwells and rooms, to utilize Bates Hall, to do their research or casual reading. I’m even warmed to the fact that the Old Corner Bookstore, across from the Old South Meeting House, once a bookstore and publisher that published Hawthorne, Emerson, Alcott, Longfellow, Oliver Wendell Holmes, and even American editions of Charles Dickens, and likely saw the presence of such literary luminaries, now houses a Chipotle fast food restaurant. It was a repeated theme that I enjoyed, these places of history still serving the present life. Even the tall masted 18th century built USS Constitution is still considered a commissioned Navy ship. A sailor, standing next to a huge 24 pounder cannon on the gun deck, told me he volunteered to serve on the ship because he wanted to get over two fears, one of talking to the public, which he was doing with me, and two of heights, which he had to overcome in order to climb the rigging and manage the sails, which they apparently still unfurl. The ship is still taken out occasionally for ceremonial duty, or just to turn her around. Even so she is really just a floating museum. Most of the cannons, named by the weight measure of their cannon balls, are replicas unable to fire a projectile. But it is telling that the Navy would go through the pretense of calling her “commissioned.”

Longfellow’s Lonely Busts

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s house in Cambridge had an impressive pedigree of inhabitants at one time and yet the busts of Sophocles, Raphael, and Shakespeare looked lonely and likely no longer inspired anyone. It seems to me a bust needs to be there gazing upon the room of its inhabitants every day to truly inspire. Even before Longfellow owned the house he rented a couple of rooms there while a faculty member at Harvard. He was thrilled that he inhabited rooms that George and Martha Washington lived in while the house was, in a previous generation, the headquarters of the newly organized Continental Army during the siege of Boston. But while Longfellow was a tenant it was a truly lived in place. Now, I feel, it is stagnated as a place of history that National Park personnel traipse the tourists through.

Empty Frames of Mrs. Gardner

The art on the walls of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in the Back Bay do inspire. On the previous Boston visit with my folks my mother grabbed one of the fold out stools so she could carefully gaze at a Whistler composition in the Yellow Room. She’s a painter herself. The museum is decorated more like perhaps the houses of the ultra-rich of the past, every space filled with pieces from the collection. And yet the highlight of the museum, the Venetian Courtyard Garden with its classical sculptures and arrangements of exotic plants, and September’s lavender bellflower blooms, left me a little cold. We are not allowed to walk into its airy, illuminated space, as we stand on the other side of the chain railing. Beyond the fact that it is a depiction of Medusa, a finely crafted mosaic in the center of the garden did not delight me as much as the mosaic I saw the day before at the entrance to Carmelina’s Italian restaurant, on Hanover Street in the North End. It was the face and wings of a seraphim encircled with three bare legs. A few tiles were missing as I stepped on it to inquire on the waiting time for a table.

As it is, some of the dictates of these movers, shakers, and philanthropists, like Isabella Stewart Gardner, try to freeze elements of their endeavors, and it causes holes in the fabric of their legacies. She carefully arranged her collections in the Venetian Renaissance palace style mansion and then she established a million dollar endowment on her passing, stipulating that the aesthetics and arrangement were to remain as she set them. In the 1990s one of the largest art thefts in history occurred at the Gardner. In the Dutch Room there is now an empty frame in front of a chair, where her first acquisition, Vermeer’s The Concert, used to hang. A magnificent Rembrandt seascape called the The Storm on the Sea of Galilee, which would glow with the fear of the disciples in the torrents of Nature’s wrath, in contrast to the divine calm of Christ, is now a sizable empty frame, framing the wall paper pattern behind it. Another sizable Rembrandt work on the same wall has its barren surrogate of paintingless frame, almost as if to balance the wall with the holes in its display. I appreciate the need to keep the theft in the memory of the institution, as the pieces have never been recovered, but time passes and things change. Is it really that alternative Dutch pieces can’t be acquired honoring Mrs. Gardner’s collecting criterion? It bars the living skills of today’s museum curators.

Repurpose and Restoration

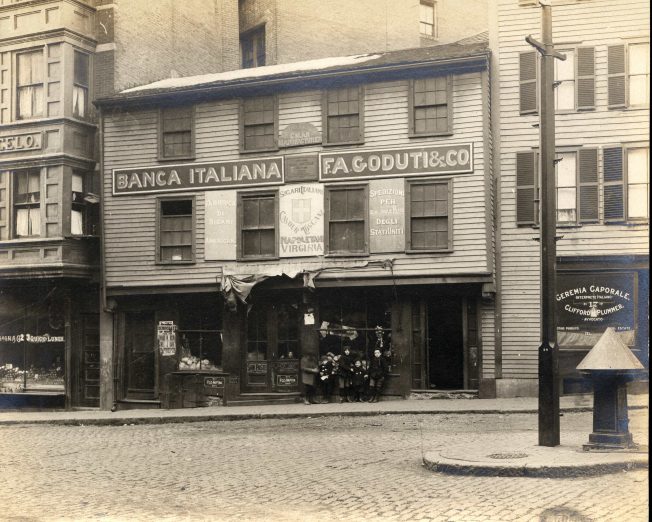

This movement of change that can’t be denied can be seen in old photographs of these historic buildings. Paul Revere’s house in the North End became tenement housing, with various first floor shops, and then it was an Italian bank. Its restoration returns it to something we might imagine it was in the time of the Sons of Liberty. I’d like to think with the help of curators and historians these places are “restored” to what they once were. But when we see photos of the Old State House as an insurance agency, clothing wareroom, and offices of the United States Telegraph Co., you know extensive alterations were made to accommodate these businesses. We have to trust their restoration somehow reenacts what they once were during the time they are being depicted. And yet when we learn that they became veterans of mundane and commercial use, we perhaps have more kinship with them.

The National Park guide at the birthplace of both John Adams and John Quincy Adams, in Quincy, just south of Boston, claimed extra wide floor boards in these old houses indicated something perhaps more original. It does make one wonder how authentic are the dark old looking rafters in Revere’s home. But how much authenticity must we demand of wood under the inevitable forces of decay. It’s why the Japanese have perfected the art of restoration by continuously renewing the old temples of Kyoto. The way they are assembled does not change, but new wood is eventually swapped for old wood. The DNA of its original construction is followed as close as can be done. Still restoration is a reenactment of a particular time that is favored by the present affections of the popular imagination. It is a kind of discrimination based on the myths we favor of certain bygone days.

Nihonmachi or Old Spanish Days

In the town that I reside, there is an old Spanish fort of sorts, it was originally built to house the soldiers and armaments that, in addition to the protection of the Spanish Mission and town, were also intended to keep the population of the indigenous people under the realm and force of the Franciscan padres and their Mission. But the Presidio, as it was called, that is there now is wholly a reenactment, a complete resurrection from the ground up. After the original Presidio fell into disuse and decay the town eventually demolished it and an immigrant community rose in its place. Nihonmachi, or Japantown, became a thriving section of Santa Barbara with a Buddhist church, a restaurant, a hotel, tenement housing, grocery store, and several other businesses run by Japanese Americans. During and after World War II the community was dispersed by first their internment in camps and then later by the town’s rejection to their return. Santa Barbara, somewhere in the first half of the 20th century, increasingly began to highlight its Spanish colonial period. The Old Spanish Days fiesta, carried out every summer, attracted visitors from all over Southern California and beyond. The city’s architectural designs for new builders narrowed to a few choices that reflected adobe, stucco, and Mediterranean red roof tiles. Thus in the 1960s the idea of resurrecting the Presidio on the site where it originally stood, ripened until work began in 1963 with completion of the Chapel in 1985. As far as I’ve learned, they’ve tried to utilize the same building processes that would have been applied during the Spanish colonial period. Archaeological research helped the rebuilders to follow pretty closely, when it could be applied amongst the businesses of a modern town, the original layout of the fort. I myself have seen adobe bricks drying in the sun, as they continued, and still continue to restore and maintain the site. I think it is a fairly honest attempt at reviving history. And yet this is a selective history of the place. It is a story that has been judged to be more significant, to the majority of the contemporary population, than other stories of that same site. And the degree to which an historic structure is authentic can vary dramatically.

Entrepreneurial Lincoln Log Cabin

When I was a kid I remember our visit to Lincoln country. There’s a memorial in Hodgenville, Kentucky built on the supposed site of Abraham Lincoln’s birthplace, and inside the classical style monument is a log cabin for a long time purported to be the original cabin where he was born. Not only has tree ring dating of the logs determined they could not be Lincoln’s original birthplace cabin, but there is plenty of historical evidence that the logs are the product of an entrepreneurial endeavor. And the structure itself is a mixed combination of a faux Lincoln cabin and another faux cabin of the Confederate president Jefferson Davis, who was also born in another little town in Kentucky. The Davis cabin had accompanied the Lincoln one on a US tour, back when Southerners would have not been drawn to a Lincoln only exhibit. At the end of the tour the logs were inadvertently mixed up. The National Park no longer claims the cabin is the original, but then my memory of childhood awe at standing next to his original infant home feels on some level a hoodwink. One starts to wonder at the level of authenticity of any historical artefact. And from there to the “truth” of so many historical facts that were conveyed to build up one’s patriotic identity. Or any identity that we might assume to be. Just listen to a lively reading of Frederick Douglass’s 1852 Independence Day keynote address to a Rochester, NY crowd, and you’ll get a different perspective on the meaning of the Fourth of July. It is a righteously indignant haranguing on the hypocrisy of that day’s celebration in the light of slavery’s continued existence.

Extra Wide Floor Boards

The turn of the 20th century “Lincoln cabin” entrepreneurs purportedly used logs from an old cabin very near the sinking spring of Lincoln’s recorded birthplace. We might assume at the time there was possibly even a hope that these logs, or a few, were recycled logs of his early family’s actual cabin. I would perhaps be generous in suggesting duplicity was not in the minds of the cabin assemblers. How much of the wood of the original 1775 farmhouses along the Battle Road Trail are a part of the now existing structures? Whether or not those extra wide floor boards in the birthplace homes of John Adams and his presidential son in Quincy are possibly more original or closer to the time that these men and their families lived, toiled, and aspired, the houses themselves were eventually rented out to tenants up to the end of the 19th century, until they became purely historic structures. They needed and need up keep that amounts to a slow but steady swapping out of rotted and decayed parts for new parts. Perhaps the chimney and hearth in the older structure was the original built in 1681. However its authenticity, I felt more attuned to an Adams family home in my imagination, as filled with the life conveyed in David McCullough’s biography of John Adams. Still I perked up at the facsimile of the Massachusetts Constitution, that Adams primarily drafted here, sitting on a table in the house John and Abigail raised their children. But the artefact quality of the structures left me again missing that breath of life we find in the ordinary spaces we live.

I recall seeing a suggestion in one of the pamphlets for the Adams National Historic Park that you should drive from the Old House at Peacefield, the estate the Adams family acquired after his years as a diplomat in Europe, across town to the Birthplaces. They used to provide a shuttle transporting the visitors between the two locations. Certainly a service for the accessibility-challenged, but for everyone? This is how we try to surgically separate history from our present day surroundings and experience. As if one is mundane and the other extramundane, and the two should not mix.

The President’s Trail Through Downtown Quincy

We took the Red Line down to Quincy from our accommodations in Dorchester. A young woman dressed in pink was intrigued with my companion’s nationality and chatted with us as we slowly shuttled over and south of the Neponset River. She was off to see the Barbie film with her friend. Once in Quincy we had no car to jettison ourselves between sites of the late 18th and early 19th century. We walked something called the President’s Trail, which was just a pedestrian’s view of downtown Quincy and its business environs. Barber shops, Chinese restaurants, gas stations, auto part stores, clinics, apartment complexes, Baptist parish, and on and on. Someone said the Birthplaces are worth a visit, but it’s all built up around the houses, as if the presence of a grown contemporary Quincy where there was once 188 acres of corn, wheat, and barley, is somehow a regrettable unavoidance. The living town was not much different, to the casual eye, than the Midwest towns I grew up in, but it’s everyday living quality is what seems a phantom inside many of the historical sites. We saw the people of Quincy and accoutrements of their lives in breathing, living color. There were things that reinforced the patriotism, like the monuments to 20th and 21st century soldiers at the General’s Bridge, apparently many high ranking officers have been born and raised in Quincy. But there were also impressions that conveyed changing demographics, like the preponderance of Chinese and other Asian groups. Our visit would just be missing out on Quincy’s Chinese inspired August Moon Festival, which we saw posters for as we walked through Quincy Square.

It’s a Small World, Dorchester

Our Airbnb accommodation in Dorchester was chosen mainly for its price, description of comfort, and its location near enough to the “T”, the mass transit system. In a book surveying historic buildings of Boston I saw that the oldest structure in Boston, a timber-framed place called the James Blake House built in 1661, was only a few blocks away. One night early in our trip we decided to walk our temporary neighborhood of Dorchester, with the house as one of the objects to encounter. The walk turned out to be fairly extensive and we encountered a wide range of ethnicities, mainly hearing the languages spoken. Spanish, Portuguese, Haitian and Cape Verde Creole, and Vietnamese. We walked through the African American area of Roxbury, and the Vietnamese American area of Savin Hill. Of course the Irish are still represented here, and there’s a Polish area of Dorchester. This is living history. The history of immigration still heard in the shop keeper talking to the customer. There was a soccer game being played by teams that looked as though they could be from any Latin American country. My companion, who hails from an Asian country, sought out a Vietnamese grocery store to find produce and Chinese sausages for our pan fried breakfast dishes. It’s the kind of “history” you don’t necessarily anticipate, but it tends to be the more intriguing. There is an authenticity that breathes, that we can truly enjoy, when we banish xenophobic tendencies.

Who’s this Edward Everett?

Next to the Blake House in Dorchester is a statue of Edward Everett, the 19th century politician who served as a Massachusetts governor, a congress man, and a Secretary of State, before the Civil War. He was born very close nearby. Trees obscure the statue from view, the locals perhaps oblivious to whomever the bronze figure represents. There’s a statue of a giant pear a few yards away at Edward Everett Square, more prominent and relatable to the immigrant population, or to any population. Still the name is there. He was a popular orator in his time. How do we resurrect history into something that feels more alive than a place name and tree branch obscured patina covered bronze figure, with a hand raised toward oblivion? There’s a four volume set of his Orations and speeches on various occasions. Seemingly out of print. Not a single review in Amazon. Its available free online through the University of Michigan. For a tiny few it may be of interest to read. And for that tiny few they are hearing the direct thoughts of the once popular orator. They are thoughts of another age, but how much is relatable to our own age? I’ve not read any Edward Everett. Due to his obscurity in the annals of history perhaps his writing is not so compelling. But he did teach and inspire a young Emerson when he taught at Harvard.

Emerson’s Mark On the American Psyche

I have revisited Emerson’s Nature and though sometimes I still struggled, I discovered its inspiring tone.

“How does Nature deify us with a few and cheap elements! Give me health and a day and I will make the pomp of emperors ridiculous.”

For an avid hiker in any age this strikes a chord of perfect truth. I can see a direct correlation between his words, meant to inspire American artists, writers, and the common people, to leave off the aesthetic accomplishments of the Europeans and find vaulted value in the natural treasures of the North American continent, and myself as a little kid in Michigan returning again and again to gape at the color photos in a 1975 edition of The New America’s Wonderlands, Our National Parks. I longed to see and experience these places. Emerson makes the case for this longing.

“Why should not we also enjoy an original relation to the universe? Why should not we have a poetry and philosophy of insight and not of tradition, and a religion by revelation to us, and not the history of theirs?”

Emerson inspired American landscape artists like Thomas Moran, Frederic Edwin Church, and photographer Carleton Watkins to seek out the natural beauty of the continent, in many cases heading west, and reflecting that sublime beauty, using either oil paints or the glass plate. Their art would reflect the grandeur and the worthy uniqueness of the experience. I too was inspired to head west and I may have had a few reasons, but perhaps those images of the natural world of the American west loomed larger in my imagination than I give it credit. Perhaps it’s what set this boy’s mind to wondering toward wandering. I’m of the type that looks for revelations and philosophies of insight that are my own. And this takes me away from my origins into more wide open spaces.

Bones Among the Roots, Light in the Leaves

The fleeting or maybe less realized inspiration emanating from the floor boards, busts, and portraits in these famous homes and structures, somehow resonated more palpably with me in the old cemeteries scattered with the bones of American patriots or 19th century authors. My first visit to the Granary Burial Grounds was a festive atmosphere, as the tourists marveled at the tombstones of Samuel Adams, John Hancock, and the victims of the Boston Massacre. Somehow, when we see these graves the characters rise like living reliefs out of the national mythos our nation’s founding has become. Perhaps it is the rays of streaming sunlight, illuminating the skull and crossbones of the memento mori reliefs, that give the cemeteries that here and now quality missing in those old corridors and rooms. The maple and elm leaves dancing in the breeze animate the space between our ordinary but respiring lives and the set in granite notions, high ideals, spur to action, and inspiring words of those past centuries. I don’t know why the living roots curling around the little modest headstone at Sleepy Hollow in Concord, that states simply “Henry,” should be a catalyst to my literary endeavors, but I felt a true kinship to Thoreau and Emerson after walking Author’s Ridge. I believe it spurs on my pen and is more kindling next to the hearth of my relationship with the sublime natural world.

Perhaps that is what these old buildings, artefacts, and places do for us. They point back at times that seem like another world, but come more alive and relatable when we hear the direct words from the primary sources of the people living in those houses, building, and places, in those times. We may not get all the references, but the sensibilities, impressions, and responses to those times give us a window into how it was experienced. It is how we recognize the values we share with our ancestors, and actually gives us insight into who and what we are now. How and why we do the things and behave the way we behave now.

The Amiable Adams Family Crypt Guide

One of the most endearing ways that history comes alive in these historical regions is when they are reflected in the actual people we meet. One of the more spontaneous activities we did was to visit the United First Parish Church in Quincy. In the basement is the crypt of John Adams and John Quincy Adams and their First Ladies. I knew it was in Quincy somewhere, but I hadn’t planned on a visit. I remember family visits to president’s graves to be a rather somber affair. Lincoln’s mausoleum and Kennedy’s eternal flame perhaps had the pall of tragic premature death, but even George Washington’s crypt at Mount Vernon when I was thirteen seemed a place where our silent reverence was required, but it somehow limited what my adolescent mind could reflect upon. Perhaps my fondness for occasional cemetery visits, and an appreciation of the sentiments of memento mori, the reminder that all is impermanent, including your own life, hadn’t matured yet.

After reading David McCullough’s biography on John Adams I included a visit to Quincy and his birthplace and home to our itinerary. After exiting the MBTA station at Quincy Center we discovered the President’s Church a few yards away. Upon entering a couple of gentleman sat at a table. Peering inside the still active church we saw no one else. One of the men at the table, a boisterous smiling fellow, offered to give us a tour. He was a member of the congregation, a Unitarian Universalist, a Christianity so dissipated from the codified Christianity that I was raised in, that it resembles a religion of Humanists, inspired by the teachings of Jesus, as well as other religions and spiritual traditions. John Adams originally provided the funding for the church and John Quincy Adams still had a pew marked designated for him and his family. It had that New England meeting hall ambiance. Something elegant yet plain. No iconography, but it had a white ceiling with plaster flower blooms and a grand mahogany altar. A pipe organ’s brass pipes glinted in the balcony. Our guide explained a little his brand of Unitarianism by remarking that John Adams would never have denied a person the freedom to worship anyway they’d like. I don’t know how similar Adams’ Unitarianism was to our guide’s spiritual practice, but I felt we were seeing the progression of that religious liberalism.

We soon followed him down to the crypt, which was surprisingly tight quarters, but brightly lit. We were not separated from the tombs by a wrought iron barrier but quite intimate with these granite sarcophagi of John Adams, Abigail Adams, John Quincy Adams, and his First Lady Louisa Catherine Adams. Our guide rubbed the surface of Abigail’s tomb as he accounted a little the biographies of these first families. At some point he said you could tell Abigail was the favorite, as her sarcophagus showed signs of the most human caress. Soon he turned to asking where we were from and recalling fondly a trip he’d made to California. It all seemed so friendly and warm our visit to the crypt, quite the opposite of my past experiences of this type. Our guide had that wonderful Boston accent suggesting we visit the Fogg, the free aht museum at Hahvahd, a place he was once employed. I couldn’t help but feel our guide was in some way channeling John Adams, perhaps intentionally or perhaps by just being a Quinconian.

Whatever kind of impression one might get of John Adams from reading McCullough’s book or watching the HBO miniseries, we can fairly assume he had the gift of the gab. He may have sometimes lapsed into vanity, but he did not seem an overly pretentious man. Thomas Jefferson, in a letter to James Madison, two men who were eventually politically opposed to Adams, once remarked, after spending some time with Adams on their mutual diplomacy in Paris, that, beside all of Adams’s faults Jefferson relayed in the letter, “He is so amiable that I pronounce you will love him if ever you become acquainted with him.” Even after their bitter political rivalry they reignited a friendship in their old age that would last until they both passed away.

As we left Quincy I reflected on the visit. It was the interaction with the guide, the present day Quincy fellow, that gave life to that site of historical significance. In the words of Adams sometimes friend Jefferson, “I am increasingly persuaded that the earth belongs exclusively to the living…” The visit to the old tombs would not have made much of an impression, lying there in the basement of the church, without the encounter of our contemporary ‘John Adams.’

Living Boston

All of these stories that we tell ourselves of our past, they convey meanings of perhaps why we believe, behave, and live the way we do, but they are only stories. Stories told in the light of certain inclinations of the times and places that the events arose, as well as inclinations that arise as the stories are retold, refashioned, and reimagined. History is seemingly a plastic thing. And what we are consuming when we visit these historic places are elaborate sketches, sometimes drawn with metaphorical charcoal derived from the actual stuff of those times. We may still have reverence and marvel at old stones and rafters, but perhaps that reverence, however concocted by the popular imagination of a people’s history, can be recognized in the ordinary places and structures of our mundane lives. We may assume life in those extraordinary times, were realized moment to moment in the same fashion as we experience our lives. To me, that mundanity has the gift of living animation, that historical places and sites only borrow, when the living walk the foot traffic carpet through the old rooms and hallways of those old buildings.

Boston is a city of the living and the dead. The living is making or eating cannolis and lobster rolls, and sightseeing or otherwise going about their business in a modern city. And the dead are bones in the ground, place names, and characters in the stories that decorate the town and give it mystique. In Robert Lowell’s poem For the Union Dead, inspired by a memorial on the Boston Common, he depicts wasp-waisted Civil War soldiers leaning on their muskets staring down from their monuments, looking out from the scattered emptiness that is the past. And to my mind, the living fill up that emptiness by telling stories taken place, or imagined to have taken place, in the old corners, and the new corners, of this region of the Commonwealth. And if the living are keen, they can recognize the difference. Nevertheless, like the out of towners that have paid for the haunted Boston tour, they are easily lulled, by the tricorn hatted guide holding the lantern, into a softly glowing vignette vision, where history and the present are inseparable. But it all depends on the discernment of the visitor peering through that mythic vapor. To what degree is authenticity a measure, or a paint brush? And when do we decide, or even know, when its one or the other, while visiting a place like Boston, that’s both old and present.

Green, Tyler, and Ralph Waldo Emerson. Emerson’s Nature and the Artists : Idea as Landscape, Landscape as Idea. Munich: Prestel, 2021. Print.

Gettemy, C. (1905). True Story of Paul Revere, His Midnight Ride, His Arrest and

Court-Martial, His Useful Public Services. Boston, Little, Brown, and Co.

Lau-Ozawa, Koji et al. Sonzai : Japantown Santa Barbara. San Francisco, Calif: Barre Fong Designs, 2021. Film.

Dwight T. Pitcaithley, “Abraham Lincoln’s Birthplace Cabin: The Making of an American Icon” in Myth, Memory, and the Making of the American Landscape, ed. Paul A. Shackel, 244 (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2001).

With Carl Linnaeus’s categorizing hierarchy inspired by monarchy, this place is a monument to the plant kingdom. I was a botany student for a stretch. I can tell you why plants are categorized into families because of their characteristics, their similarities. Asteraceae, Orchidaceae, Pinaceae, Moraceae. But here so much of everything is packed in like a living botanical library, where all the books are seemingly stacked willy nilly. There may be a method to the jumble, but when you have to house a huge variety of cacti from the Colorado to the Atacama Desert in a few acres, it is going to get crowded. Aloes of southern Africa send their bright orange inflorescences high above the fleshy leaves, jockeying with the agaves and the bromeliads, which have their own impressive blooms. It gives me that out of context feeling museums often engender. It fatigues me. I came here for something more transcendent than plant identification. I was hoping to locate it in the Asian gardens. An artifice that strives for natural authenticity; these gardens are created for one to move silently through stillness and poise. On my way toward them I wandered through a jungle habitat, then below tall eucalyptus of the Australian Garden. Southern California is no stranger to this genus, the Tasmanian blue gum long since naturalized. It was a busy afternoon at the Huntington and the crowds milling about gave the impression there are quite a few visiting Los Angeles that would prefer the subtle excitement of botanical gardens, to the thrill of Universal Studios. And probably quite a few locals here. Although the entrance fee is a demanding $29 at the door for the day, if you split an annual membership with a friend or loved one you’d beat that price with only three yearly visits. I’d be signing up if I lived anywhere near there.

With Carl Linnaeus’s categorizing hierarchy inspired by monarchy, this place is a monument to the plant kingdom. I was a botany student for a stretch. I can tell you why plants are categorized into families because of their characteristics, their similarities. Asteraceae, Orchidaceae, Pinaceae, Moraceae. But here so much of everything is packed in like a living botanical library, where all the books are seemingly stacked willy nilly. There may be a method to the jumble, but when you have to house a huge variety of cacti from the Colorado to the Atacama Desert in a few acres, it is going to get crowded. Aloes of southern Africa send their bright orange inflorescences high above the fleshy leaves, jockeying with the agaves and the bromeliads, which have their own impressive blooms. It gives me that out of context feeling museums often engender. It fatigues me. I came here for something more transcendent than plant identification. I was hoping to locate it in the Asian gardens. An artifice that strives for natural authenticity; these gardens are created for one to move silently through stillness and poise. On my way toward them I wandered through a jungle habitat, then below tall eucalyptus of the Australian Garden. Southern California is no stranger to this genus, the Tasmanian blue gum long since naturalized. It was a busy afternoon at the Huntington and the crowds milling about gave the impression there are quite a few visiting Los Angeles that would prefer the subtle excitement of botanical gardens, to the thrill of Universal Studios. And probably quite a few locals here. Although the entrance fee is a demanding $29 at the door for the day, if you split an annual membership with a friend or loved one you’d beat that price with only three yearly visits. I’d be signing up if I lived anywhere near there.

Why would the application of water be a bad thing to financial wheeler dealers of the West Coast? The lack of water is the real fear that would melt any developer’s vision of a West Coast empire. Los Angeles exists by the grace of acquired water rights. And that is thanks to one of its modern visionaries and developers William Mulholland. As I lay on the hotel bed I lost control over my thoughts meandering through story metaphors of late 19th and early 20th century economic and political times, and they mingled with my plans for the next day. Mulholland? I did note earlier while perusing the L.A. travel guide a mention of Mulholland Drive. I had intentions of visiting sites east of Griffith Park and that road took me in the direction. The guide touted views of the city, which were mostly of San Fernando Valley I later discovered, and the chance to drive amongst the homes of Hollywood’s power players. The latter was to my mind mostly a meaningless idea, but the guide meant to lend a vague shadow of mystery to traversing the road. With my morning plans anchored to a stretch of pavement I gave myself permission to descend into the dark unconsciousness of sleep.

Why would the application of water be a bad thing to financial wheeler dealers of the West Coast? The lack of water is the real fear that would melt any developer’s vision of a West Coast empire. Los Angeles exists by the grace of acquired water rights. And that is thanks to one of its modern visionaries and developers William Mulholland. As I lay on the hotel bed I lost control over my thoughts meandering through story metaphors of late 19th and early 20th century economic and political times, and they mingled with my plans for the next day. Mulholland? I did note earlier while perusing the L.A. travel guide a mention of Mulholland Drive. I had intentions of visiting sites east of Griffith Park and that road took me in the direction. The guide touted views of the city, which were mostly of San Fernando Valley I later discovered, and the chance to drive amongst the homes of Hollywood’s power players. The latter was to my mind mostly a meaningless idea, but the guide meant to lend a vague shadow of mystery to traversing the road. With my morning plans anchored to a stretch of pavement I gave myself permission to descend into the dark unconsciousness of sleep.