Eventually it came time for my appointment with the specialist. Specialist? This is a story about you on vacation, right? Well, yes. But perhaps I should give the initial reason for this L.A. excursion in the first place. As I mentioned before, I used to dislike, even abhor L.A.. The traffic was always my excuse but I also felt the city was less than picturesque. The urban sprawl reminded me of the unfettered expansion of the human race, to the detriment of the natural world. Or at least I felt that way. I would get claustrophobic and let the congestion and busyness clog my head and thoughts. I wouldn’t have admitted or even understood that a lot of the congestion and busyness was all in my head. The kind of understanding that comes from a few years of meditation, that Path of the Eightfold that is Right Concentration. Back then I would have had zero meditation experience. The only glimpses of Buddhist thought gleaned through an evening hour show on KPFK of old recordings of Alan Watts. A Brit relocated to the West Coast, in the 1950s and 60s he was an expounder of eastern philosophy who disguised himself as a Zen Buddhist, but was more a kind of Taoist court jester. After my escape further north to Santa Barbara I was able to explore and ingest some of the teachings from various advocates, and take on more the actual practice.

Now it wasn’t the fire lookout at Desolation Peak that Japhy hooked up for Ray Smith in Dharma Bums, the novel I had with me on this L.A. excursion. A seclusion that enabled Ray to take a weak zazen with dogs in the North Carolina woods, to the guffaws of his family, and mature it on a mountain top on the edge of the Canadian border. But for me, compared to L.A., Santa Barbara was just the right kind of ‘little seaside hamlet,’ as my brother called it on a visit up from his Orange County life, to enable me to see more clearly what it is I should be doing or heading toward in life. That is, to use what Bhikkhu Bodhi, the author of that other book I was carrying, calls “wise consideration.” To see that the seeds of suffering are sown in the mind first, before they are visibly manifest. I made a switch from the manic desperation of restaurant work to the plodding shelving of bookstore work. I had lots of open wilderness with which to retreat and start to notice that the cacophony was just as much in my head, as it was out and about on the streets and places of business of the town. Meanwhile, I had no inclination whatsoever to venture down into the behemoth that was L.A./Orange County. The idea of planning a few days in the city would have been a seedling I quickly squashed with deep L.A. fear and loathing. But as I’ve mentioned before, that would have been a while back. My head is in a different place these days. And more recently I’ve been seeing a health specialist with an office in Santa Monica. I’ve been going once a month for the last few months, and while I’m down in the city I take in a sight or two and get a mouthful of L.A. cuisine. The city has grown on me. There’s plenty of interesting culture spread out amongst the sprawl. Another specialist appointment and a scheduled flight out of LAX, combined with a needed respite from a burning Santa Barbara County, funneled me toward taking the few days for this jaunt through the City of Angels.

My specialist visit a few blocks from the Comfort Inn was routine and uneventful, so I had the late afternoon to carry on with whatever I could fit in of the town. There was an exhibit at the Getty Center, just up the 405 a little north of Santa Monica, which in its own way was another draw to hit L.A. up before the end of the coming month, when a particular exhibit would head off to the Met in New York. It was titled Golden Kingdoms: Luxury Arts in the Ancient Americas. I’m writing a novel with some tangential theme of New World gold running through the plot. I had gotten word of the exhibit’s existence from a colleague and going on adventures with the excuse of research is always a nice draw. The Getty Center grounds is a unique space to be in with its Italian travertine stone, water sculptures, gardens, unique architecture and naturally lit lobbies. The Center’s history is itself the stuff of luxury arts.

With the fortune he made from the oil industry J. Paul Getty, the man infamous for initially denying a ransom payment for his kidnapped grandson, began collecting Roman statues from aristocratic Brits. These aristocrats, during the height of the British Empire, would set them up in their parlors to impress their friends and acquaintances that they should be associated with the power and influence of the Roman and Greek elites.

Eventually, long past he was declared the richest man in the world, he opened a museum in Malibu, which later became a replica of a first century Roman villa, built on a bluff in Pacific Palisades. Now years later, after his death and its consequential huge endowment, making the institution one of the richest museum trusts in the world, a complex of buildings had been built on a ridge in Brentwood, overlooking the L.A. Basin.

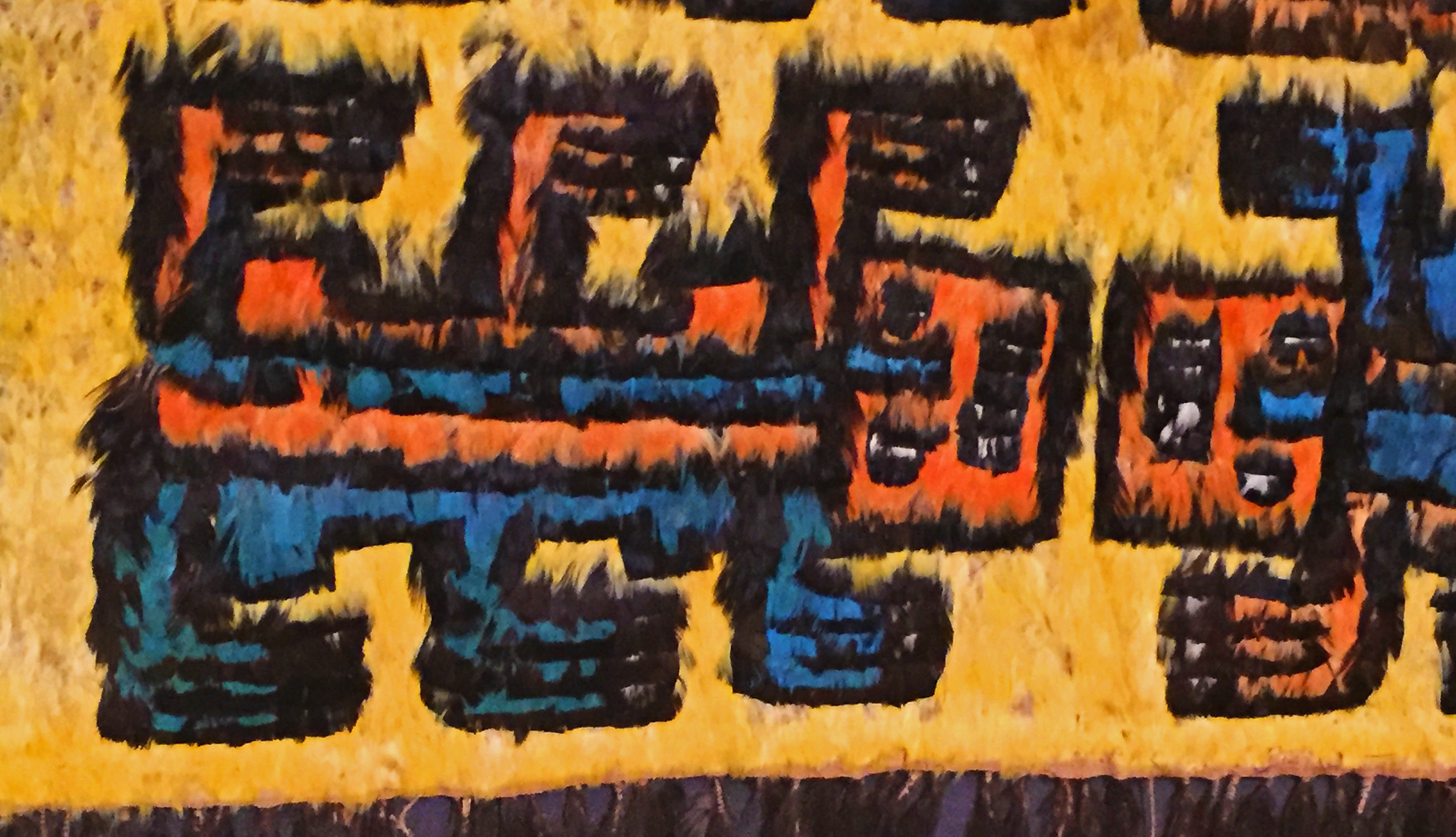

The exhibit was a fantastical collection of pieces from Latin America from 1200 BCE to the beginning of the Spanish colonial period, and stretching from southern Peru to Mexico. It was a trove of art treasures fashioned from gold, silver, jade, turquoise, and sea shells, as well as other elements of the natural world. There was Moche jewelry and Wari textiles of Peru, stirrup-spout vessels and ceramic figurines from Trujillo, golden animal figures from Colombia, Olmec jade repurposed by the Maya, the Aztecs themselves repurposing Mayan pieces. If there was an advanced civilization in Latin America going back 3.2 millennium it was represented here. And where ever you have civilization you have elites and royalty. The average Chavinian would not have been snorting psychotropic plant powder from elaborate feline-imaged snuff spoons carved of bone. The exotic bird feathered tabard would have been placed over the shoulders of a Nasca lord. The rare Aztec gold works not destroyed by the conquistadors, consisting of diminutive bell pendants and ornaments uncovered in recent excavations of the Templo Mayor, would have likely been crafted in workshops of Moctezuma’s palace at Tenochtitlan. Later, I was able to read the exhibition catalog, titled the same as the exhibit. It provided rich histories to the pieces and cultures that produced them.

To argue whether this all represents greed might be an unnecessary elaboration. We don’t know if there were ascetic monks, at least I have not read of any evidence of such things in my perusal of Latin American pre-Columbian history. There may have been some, but most urban priests of these cultures would have likely been elites wearing shiny gold body ornaments that clinked, and jade necklaces that rattled, the sounds and sights dazzling the masses as these priests and lords performed their rituals upon the altars and pyramids of the cultural centers. It sounds like priests of most cultures, at least when it comes to the decorative dress during rituals and services. No patch robe monks here. Not that Buddhists monks were innocent of acquiring riches and comforts over time. The Buddhist temples and monasteries of Asia attest to the wealth attracting power that assumptions of holiness bestow on those assumed to be holy. But this museum, itself founded by a power player, opted to exhibit the finest that pre-Colombian artists, in the employment of the royal houses, could produce from the most valuable natural material the vassal regions had to offer.

In a way, it represents perfectly what the metropolis holds near its core. Los Angeles is the second largest city in the country. Big cities attract power players. In fact, we could say they are funded by power players. The wealth they represent is the wealth achieved through lobha, a Pali word Bhikkhu Bodhi defines as “self-centered desire: the desire for pleasure and possessions,…the urge to bolster the sense of ego with power, status, and prestige.” Is the viewer, the wanderer amongst the display cases of a metropolitan museum, guilty of partaking of this lobha? It’s a question a Buddhist might ask themselves. Do cities make those attempting some level of renunciation slightly guilty, tarnished, lessened somehow? The temptations certainly are there to kick around vows that have been taken. The canon of tales from the Bible’s Prodigal Son to Johnny Cash’s Don’t Take Your Guns to Town, attest to the dangerous folly such places can induce. Bhikkhu Bodhi belongs to a sect of Buddhism that tends to hold those vows seriously. Right Action includes “abstaining from taking what is not given.” There are many layers to what is considered unwise action that breaks this vow, including fraudulence and deceitfulness. What was on display in these cases came to this exhibit through many different means. In many cases, they were originally, long ago, the result of grave robbery. You might say that is a bit of unfortunate history that does not devaluate the exhibit’s legitimacy. Fair enough. A majority of the objects in the exhibit were on loan from Latin American institutions. But a good portion were held in private collections of US citizens and institutions, like the Rockefeller Collection, Harvard’s Peabody Museum, and the whimsical sounding Dumbarton Oaks. Not to say that entire collections are illegitimately owned, but we know the manner in which valuable artifacts of these types tend to flow from the nations of their origin, to richer nations. Or whether everyone of an origin nation is in full agreement with the legitimacy of an archaeological dig carried on by a foreign institution. Even the Getty is in dispute with the Italian and Greek governments over their Roman and Greek antiquities at the Villa. A recent criminal indictment forced a curator’s resignation. But I hadn’t ingratiated my way into the presence of an English duke in his Roman statue strewn parlor. I paid a nominal $15 bucks for parking, actually $10 for arriving after 3 pm, to indulge in what only the wealthy could have seen 250 years ago. Should a citizen of very modest means not enjoy the spoils of her parent nation? Whether Krishna would allow the common man Arjuna’s province, when it comes to cultural experience, I cannot say. I think Jean Paul Getty decided so with the death purse of a modern Krishna. Other than the parking, and the gas to get there, the Center’s admission is free.

But such treasures on display to a wealthy nation’s public may do another thing that to some degree counteracts the ethical ambiguity of some if its pieces’ proprietorship. We can recognize and respect the aesthetic and artistic genius of these ancient indigenous American cultures. The exhibit itself was part of a Los Angeles wide effort among its museums and collections to recognize the values and achievements of Latin American regions and people, both historically and contemporarily, especially wise in a city with a majority Latino population.

After a while, the solid precious metal pieces were less attracting. More intriguing to me were the Moche gold ear lobes with shell and turquoise inlay in the shape of some winged Olympian-like runner with the face and beak of an owl. There was the whimsical figure made of metal and shell inlay sitting atop a spondylus shell like some pre-fall Humpty Dumpty wearing a colorful tunic, all crafted by a first millennium Wari artisan. The elegant craftsmanship and imagination of these artisans and their cultures were reflected in a variety of mediums from elegantly shaped Moche ceramic figures of mythic animals, to intricately carved limestone reliefs of exquisitely dressed and bedecked Maya queens. Even 16th century Europeans appreciated the elegance of the works that survived the dull belligerence of conquistador handling or ignorance, and somehow found their way to the cultural centers of the Old World.

It is a curious phenomenon that a greed so intense, even Cortez described it as a disease of the heart, would be so blind as to completely destroy the human element of the very objects it coveted. But of course, the Spanish were only interested in one substance, of which some of the objects were made. Near the end of the exhibit was an ingot of gold, the product of Spanish crucibles. It had all the elegance of a squared off lump of dough. The ingot was unearthed from the sediment of Mexico City and a possible candidate for the hundreds of thousands in pesos of gold bullion that became death yokes, dragging down Spaniards to drown in Lake Texcoco as they fell from the causeways of Tenotchtitlan, in the flight and fight of La Noche Triste. The wicked energy that greed has, the element the Pali canon points to as a significant source of suffering, can even lead to early, ignoble death. The Aztecs were astonished at what the Spaniards valued, these bearded men who dismissed those things of obvious beauty and craftsmanship. Textiles and jadeite carvings were completely ignored. Although the gold, this ‘excrement of the Sun,’ could be hammered or casted into many a mythic nagual, the Aztecs, like the rest of the Latin American cultures, valued more the earth colors of the raw material they used to craft their luxury arts. The jadeite, malachite, quartz, and turquoise represented the blues of water and the greens of plants, the true sources of sustenance and life. Seashells were the “daughters of the sea, the origin of all waters.” Spaniards would strip out the gold embellishing and fastening feather headdresses made of quetzal, roseate spoonbill, and fiery hummingbird, tossing the plumage to the dirt. The physical and cultural destruction was fantastical. But in Buddhist understanding there is a kilesa, the Pali word for these roots of suffering, that is just as destructive. The reason this exhibit mostly contains artifacts on loan from Latin American collections, and were recovered from excavations of temples and tombs, is that almost all surviving pieces that arrived in the Old World during La Conquista, and were valued by more enlightened Europeans, were eventually destroyed during the Protestant Reformation. Aversion, the kilesa on the opposite pole to greed, dominated the emotions of those who saw only idolatry and evil in the works of art they did not understand. This aversion, dosa to the students of the Buddha, is expressed through dis-qualities Bhikkhu Bodhi likens as “rejection, irritation, condemnation, hatred, enmity, anger, and violence.” What is even the more curious phenomenon is that both these twin towers of dukkha, have in the end the same destructive result on the living treasures of a unique and rich culture. Of course, these are the extremes of these kilesas, but even small helpings are destructive of our day to day happiness and peace of mind.

Three and a half hours wasn’t enough and I had to quickly glance at Aztec codices and regretted not having more time to gaze at the Mask of the Red Queen of Palenque. A mosaic masterpiece of jadeite and other stone inlays, crowned with a greenstone and shell headdress. The exhibit itself was strategically arranged with a gift boutique at the end, instead of relegating Pre-Colombian tomb booty look-alikes to the museum’s gift shop, with all the other souvenirs. There was still the matter of finding a Christmas gift for my mom. This was that season that is supposed to represent giving, but has a certain whiff of greed, through the prism of rampant consumerism. I had a friend from Mexico City once. He told me at the time, Mexicans weren’t into overzealous gift giving. He invited me to go with him to that metropolis for las Posadas. The stretch of days in December with family, friends, and celebration, where no one is turned away for lack of money or vacancy. Anyhow, I had been dazzled by the riches of the exhibit and succumbed to purchasing a shawl vaguely reminiscent of ancient textiles I’d just seen. Whether it becomes a pointless bit of drapery in my parent’s house was less concerning than the freedom from the pressure of obligatory gift selecting I had now achieved. Did I walk away with an idea or two to inspire my novel? I can’t say for sure. These things don’t necessarily work in such a linear way. One never knows what has been experienced in the flesh, that will later feed and clarify your imagination.

If I was an ancient Maya I would have taken the contrail from a rocket launched at Vandenberg as a good omen. As I walked to the tram and stepped down the travertine steps it lit up the evening sky above the Pacific in the form of a ghostly white stallion’s head, neck and mane. It was like a giant milky mother of pearl inlay you only get in a few places on occasion, like here in the skies of this part of Southern California.

That night I decided a more modest meal would do, so I walked down a couple of blocks from the Comfort Inn and found a fairly simple looking place that offered standard American fare. Something maybe a half notch up from a Denny’s. Coogie’s Café Santa Monica had a special about 10 dollars cheaper than my entrée the night before. A handful of older people populated a mostly empty diner. Although the salmon and rice were cooked to just the right consistency it lacked flavor. The peas in the split pea soup seemed to have been done al dente. I’m not sure if that is a culinary thing but I like my split pea soup to be rather less crunchy. I felt myself longing for the gourmet sensations of the night before. The waiter, in his thick Hispanic accent, was gracious, even warm and friendly, inquiring where I would be spending Christmas and with whom. In the end, due to his Right Speech, I had to leave the full 20% tip. It wasn’t his fault the food was bland. He just brought it to me. But perhaps that is ultimately the thing about the Buddhist Intention of Renunciation while on vacation. It’s not that we should avoid extravagant meals, but that we should respectfully, even gratefully, accept the dining choice we’ve made and what has been brought to us. Sending an overdone steak back to the kitchen is not a problem, but we should do it with a smile. And we should make the most of what has been provided. But being a food critic is probably not something I should pursue. Foodies and renunciation are two concepts that are hard to reconcile.

That was it. I had exhausted my day. Suffice it to say I’m reaching this thing they call middle age. I have little interest in the nightlife of a city. I know L.A. is supposed to be a town of bar and club fun, and maybe there is somewhere in the sea of happening places such a place that fits just right for a rather detached, mild-mannered man, adverse to over excitement. But the work and inevitable initial failed attempts to find such a place in this vast sprawl of a city, is beyond my capacity to enjoy. So I caught a little more Antique Road Show and the tail end of this holiday season’s running of the Wizard of Oz, on the room TV, before going to sleep.

As I drifted off to my own land of Oz I recalled a cultural anthropologist explaining a theory that the Wizard of Oz, the original novel, was really an allegory of the 1896 William Jennings Bryan presidential campaign. Bimetalism, the addition of silver to the gold standard to pump needed cash into the economy, was the front and center issue of his campaign. Dorothy’s family represented the mortgaged Midwest farmer. The Tinman was the proletariat without the heart to support their brethren, the indebted farmer. The Lion was the political elite without the courage to assist the farmers. The Scarecrow was of course another representation of the farmers, apparently without the brains to avoid the situation to which they found themselves. The Wicked Witches of the East and West were the bankers and developers of the coasts who were, according to the author, the real perpetrators of the financial crash that brought on the Panic of 1893, the catalyst for the farmer’s dire situation. I couldn’t tell you what everything represented in the story. And probably the film producers had no inclinations to these original metaphors, if they were in fact originally intended by the author, when they built their Kansas and Oz in Culver City studios, just a few blocks south and then up Venice Boulevard, from where I was sleeping at the Comfort Inn in Santa Monica. But I had a question about how the demise of the Wicked Witch of the West fit in with the allegory.  Why would the application of water be a bad thing to financial wheeler dealers of the West Coast? The lack of water is the real fear that would melt any developer’s vision of a West Coast empire. Los Angeles exists by the grace of acquired water rights. And that is thanks to one of its modern visionaries and developers William Mulholland. As I lay on the hotel bed I lost control over my thoughts meandering through story metaphors of late 19th and early 20th century economic and political times, and they mingled with my plans for the next day. Mulholland? I did note earlier while perusing the L.A. travel guide a mention of Mulholland Drive. I had intentions of visiting sites east of Griffith Park and that road took me in the direction. The guide touted views of the city, which were mostly of San Fernando Valley I later discovered, and the chance to drive amongst the homes of Hollywood’s power players. The latter was to my mind mostly a meaningless idea, but the guide meant to lend a vague shadow of mystery to traversing the road. With my morning plans anchored to a stretch of pavement I gave myself permission to descend into the dark unconsciousness of sleep.

Why would the application of water be a bad thing to financial wheeler dealers of the West Coast? The lack of water is the real fear that would melt any developer’s vision of a West Coast empire. Los Angeles exists by the grace of acquired water rights. And that is thanks to one of its modern visionaries and developers William Mulholland. As I lay on the hotel bed I lost control over my thoughts meandering through story metaphors of late 19th and early 20th century economic and political times, and they mingled with my plans for the next day. Mulholland? I did note earlier while perusing the L.A. travel guide a mention of Mulholland Drive. I had intentions of visiting sites east of Griffith Park and that road took me in the direction. The guide touted views of the city, which were mostly of San Fernando Valley I later discovered, and the chance to drive amongst the homes of Hollywood’s power players. The latter was to my mind mostly a meaningless idea, but the guide meant to lend a vague shadow of mystery to traversing the road. With my morning plans anchored to a stretch of pavement I gave myself permission to descend into the dark unconsciousness of sleep.